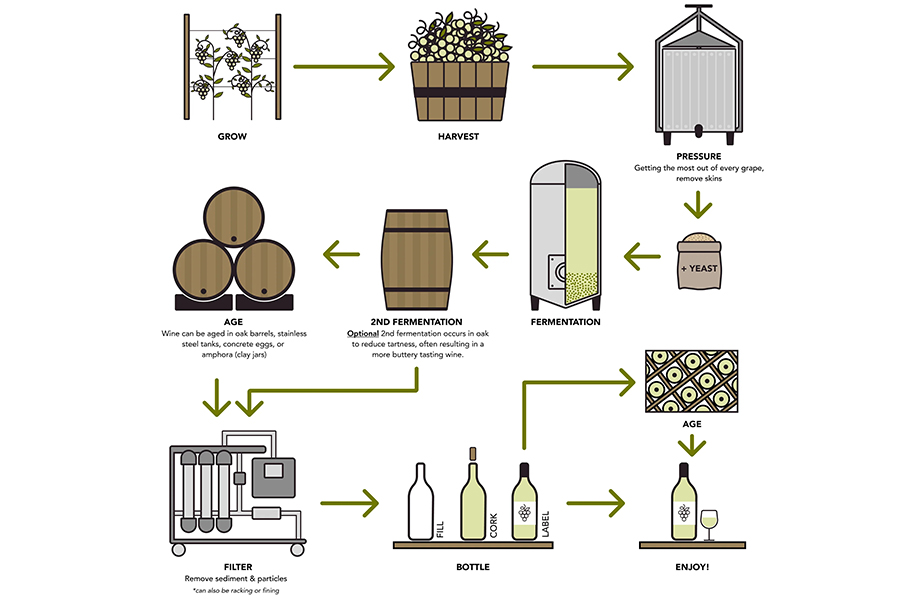

The production of white wine is characterized by early juice separation, meticulous fermentation control, and carefully planned stylistic choices. Unlike red wine, which ferments with skins and seeds, white wine is made using only grape juice, allowing acidity, aroma, and freshness to take center stage. From harvest to bottling, every step plays a crucial role in shaping the wine’s final character.

1. Harvest and Grape Selection

The quality of white wine begins in the vineyard. The ideal harvest window occurs when sugar levels reach 17–24 °Brix, a range that balances potential alcohol, acidity, and flavor development. After harvest, grapes are carefully inspected. Shriveled, damaged, rotten, or moldy clusters are removed to prevent microbial contamination and the development of off-flavors. Professional winemakers typically rely on sorting rather than washing, as washing can dilute the juice and remove naturally beneficial compounds.

2. Pressing and Juice Separation

A defining characteristic of white winemaking is that grapes are pressed before fermentation to separate the juice from the skins, seeds, and pulp.

There are two primary processing methods:

Crush and Destem Before Pressing

This is the most common approach. Grapes are gently crushed to release juice, while stems are removed to avoid bitterness and vegetal flavors.

Whole-Cluster Pressing

Entire grape bunches are pressed without crushing. This method yields cleaner, more delicate juice but lower extraction rates and is often used for premium or aromatic white wines.

The liquid obtained after pressing—containing juice and fine solids—is known as grape must.

3. Must Analysis and Adjustment

Before fermentation begins, the grape must is analyzed for three key parameters:

· pH – indicates acidity and microbial stability

· Total Acidity (TA) – influences freshness, structure, and balance

· Brix (°Brix) – measures sugar concentration and potential alcohol

To produce a well-balanced white wine, these values must fall within appropriate ranges. If they do not, adjustments such as acid correction or sugar modification are made at this stage to ensure proper fermentation and a harmonious final wine.

4. Sulfur Dioxide Addition and Yeast Inoculation

To protect the grape must and ensure a controlled fermentation, a measured amount of sulfur dioxide (SO₂)—commonly added in the form of potassium metabisulfite—is introduced. This inhibits unwanted wild yeasts and bacteria that could cause spoilage or undesirable aromas.

Although wild yeasts naturally exist in vineyards, on equipment, and in winery air, their behavior is unpredictable. For this reason, most white wines are fermented using selected commercial yeast strains, chosen for their reliability, fermentation efficiency, and positive flavor contribution.

5. Alcoholic Fermentation

After yeast inoculation, fermentation typically begins within 1–3 days, with temperature being the primary influencing factor. Yeast metabolism is highly temperature-dependent:

Cool fermentation slows yeast activity and helps preserve delicate aromas

Warm fermentation accelerates sugar conversion but requires close monitoring

During alcoholic fermentation, yeast converts grape sugars into alcohol and carbon dioxide, forming the wine’s fundamental structure and aromatic profile.

6. Malolactic Fermentation (Optional)

Once alcoholic fermentation is complete, the winemaker may decide whether to initiate malolactic fermentation (MLF)—a secondary process that converts sharp malic acid into softer lactic acid.

· No MLF: preserves crisp acidity and bright fruit expression

· Partial MLF: balances freshness with added complexity

Full MLF: results in a rounder mouthfeel and greater depth, commonly seen in styles such as Burgundian Chardonnay

If malolactic fermentation is not desired, sulfites are added immediately after primary fermentation to inhibit lactic acid bacteria. If MLF is chosen, specific bacteria are inoculated, and sulfites are added only after the process is complete.

7. Post-Fermentation Adjustments and Lees Management

After fermentation, the wine is reassessed and adjusted as needed for:

· pH

· Total acidity

· Sulfur dioxide levels

At this stage, the winemaker determines the aging approach:

Racking: separating the wine from settled lees to improve clarity and purity

Lees aging (sur lie): stirring the lees to enhance texture, mouthfeel, and complexity

8. Aging and Storage

White wine aging is a controlled and closely monitored process that typically includes maintaining protective sulfur dioxide levels, storing the wine at a stable temperature of approximately 13°C (55°F), and conducting regular tastings and analyses every 4–6 weeks.

Depending on the wine style, aging generally lasts:

Around 6 months for fresh, fruit-driven wines without oak or lees aging

Approximately 9–12 months for more complex wines aged in oak barrels and/or on lees

During this period, flavors gradually integrate, and the wine moves toward balance and maturity.

9. Bottling Preparation and Bottling

When the wine reaches its ideal sensory profile, final laboratory analyses are conducted and any necessary adjustments are completed. This step is critical, as no changes can be made once the wine is bottled.

After clarification, stabilization, and final sulfur calibration, the wine is bottled—marking the successful completion of its journey from grape juice to finished white wine.

White winemaking represents a delicate balance between science, technique, and stylistic intent. From early juice separation and controlled fermentation to optional malolactic fermentation and carefully managed aging, every decision influences the wine’s final character. It is this precision and attention to detail that gives white wines their exceptional freshness, elegance, and diversity.